Learning in Covid-Time

“Why should we – indeed how can we – continue to take an interest in these placid occupations when the lives of our friends and the liberties of Europe are in the balance?”

These are words taken from C.S. Lewis’ sermon Learning in Wartime, given on the eve of the outbreak of World War II, in light of uncertainty about the continuation of universities. In 2020, universities face the same question: Should we stay open? Though a starkly different set of circumstances to a world war, the novel coronavirus has turned our worlds upside down as countries have locked their doors; the familiar furniture of our lives has been upturned and we’ve had to adjust to a new normal. We’ve had to realise that we are not in control.

In the face of seemingly abnormal situations, we can feel like the “normal” tasks of our everyday life- engaging with the world around us through literature, film, music, relationships- is pretty futile. What good could my reading a fiction novel do for the global crisis that is Covid-19? Lewis challenges us to seek to learn, in times of war and crisis, in demonstrating how crisis does nothing to fundamentally change the human condition, and in suggesting that learning can in fact give us insight into something much greater than ourselves- something more life-altering than war, and ultimately, something more powerful than death.

“The war creates no absolutely new situation; it simply aggravates the permanent human situation so that we can no longer ignore it."

In the midst of Covid-19, old rules for how we live have been replaced by new ones. Lifestyles may have been adjusted to fit around Corona’s schedule, but the things that make humans, human, haven’t gone away. We think, we feel, we breathe, even though the circumstances within which we do these things may have changed. A change in circumstances can make us feel that we must become entirely consumed by the situation at hand, be it a breakup, the loss of a loved one, be it war or coronavirus. At times, we can feel that in order to address the crisis we are faced with, we must command all of our attention to thinking about it, obsessing over it, and finding a solution to it. While immersing ourselves in the problem we are confronted with can be helpful, at some point, it becomes unproductive. C.S. Lewis helpfully illustrates this point with an anecdote:

“Before I went to the last war, I certainly expected that my life in the trenches would, in some serious sense, be all war. In fact, I found that the nearer you got to the front line the less everyone spoke and thought of the allied cause and the progress of the campaign…”

Enlisted in the army or not, Lewis argues, he never ceased to be a man. “The war will fail to absorb our whole attention because it is a finite object and, therefore, intrinsically unfitted to support the whole attention of the human soul.” As humans, we have an “appetite” for deeper understanding which does not disappear in the face of crisis, but if we attempt to “suspend [our] whole intellectual and aesthetic activity, [we will] only succeed in substituting a worse cultural life for a better."

Put simply: “If you don’t read good books, you will read bad ones.”

C.S. Lewis points out an intrinsic humanity which remains unchanging, an inherent desire for more. A yearning of the soul for answers. A grasping at something bigger, perhaps higher… "

“Human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice. Human culture has always had to exist under the shadow of something infinitely more important than itself”. War, Lewis says, makes us aware of our mortality, and ultimately, our humanity. In a similar way, coronavirus has forced us to face ourselves in ways we have not had to for a long time, perhaps ever. “Abnormal” circumstances necessitate a shift in perspective that forces us to engage with reality. War, or coronavirus, does not make it more likely that we will die- death is one thing we can all be absolutely certain of- but it does, as Lewis points out “force us to remember it."

So, perhaps we should do just that: engage with our humanity and ask questions that we have never dared to ask, rather than become paralysed into inaction by the crisis at hand. Crisis is no new human phenomenon, and we must persevere in a pursuit of knowledge in the face of this current one; “If we let ourselves, we shall always be waiting for some distraction or other to end before we can really get down to our work."

It seems very tempting to wait until things get a little easier before we start asking big questions. We could just, in the words of Shaun (Shaun of the Dead) "go to the Winchester, have a nice cold pint, and wait for this all to blow over." Apart from the fact that the pubs are closed, this approach isn't the most fruitful. We can wait our whole lives for the conditions for learning to be perfect, but C.S. Lewis argues that, in fact, "favourable conditions never come.”

“The only people who achieve much are those who want knowledge so badly that they seek it while the conditions are still unfavourable.”

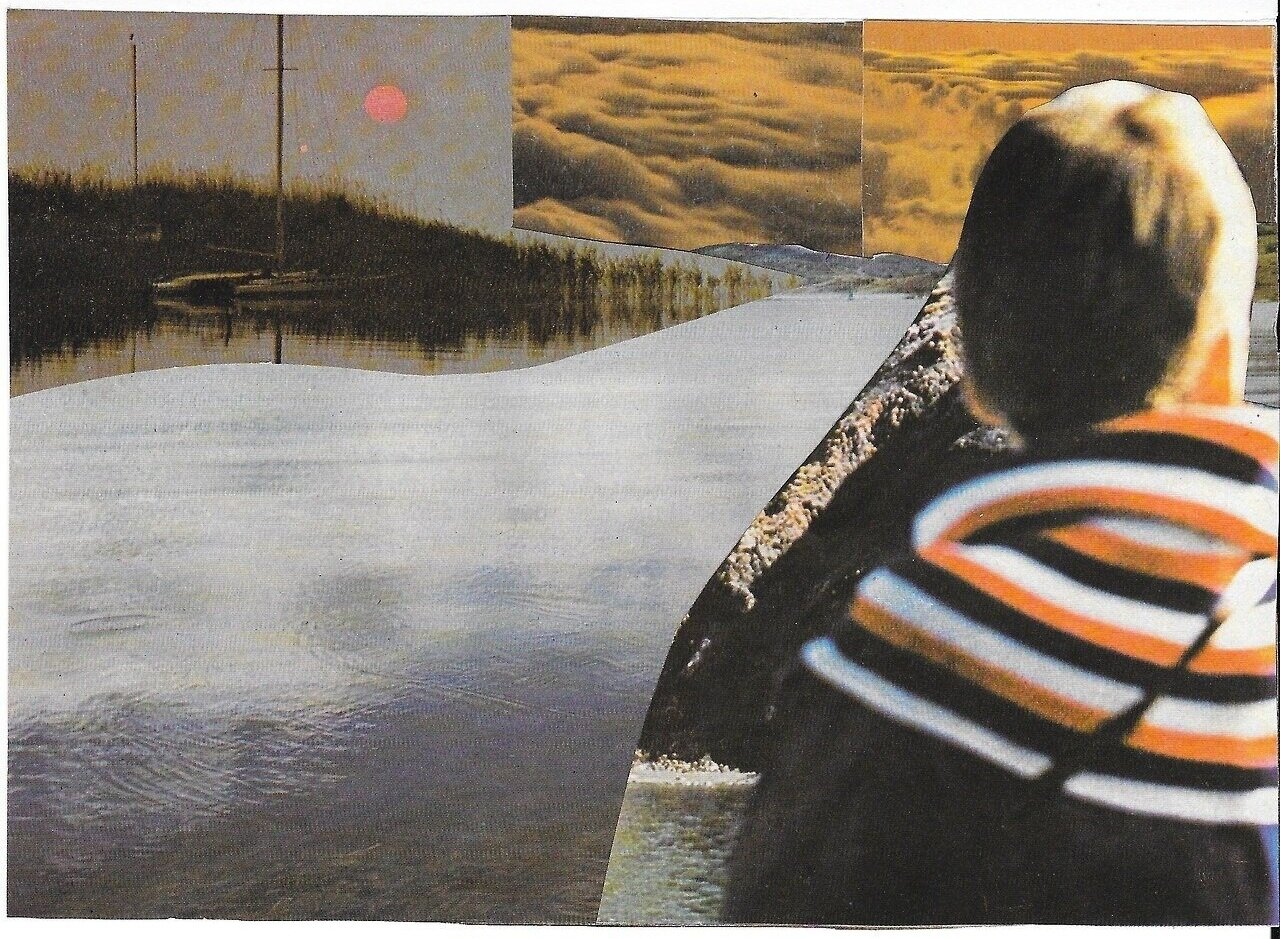

Amana Moore is a third year student at Durham University studying English Literature and French. You can find Amana’s art here.