Tracey Emin: I Thrive on Solitude

Tracey Emin has put out her first ever online exhibition, I Thrive On Solitude, on the White Cube website. The series, articulated in Emin’s characteristic sprawling and languid acrylics, shows the work Emin has produced while living alone in London during the coronavirus lockdown. The works signify a “transference of emotions and place,” acting as potent autopsies of the stasis of the last few months, and candid reflections on the ramifications of this period on her own mental health.

I was as surprised as I was moved by this breathtaking body of work. The artist rose to fame with the Young British Artists in the 1990s, asserting her role as the brutally honest, establishment-upsetting enfant terrible of the British art scene. Her early works, the most notable of which is the infamous My Bed (1998), spoke of her adolescent and early adult experiences with depression and trauma. They re-calibrated my own understanding of mental health and softened the sharp blow of my own depression when it hit me in my mid teens, overturning the shame associated with the messy lethargy of mental illness. But this authenticity was, as is common, heavily diluted by her celebrity. The artist that once willfully rejected traditional dogmas became the Eranda Professor of Drawing at the Royal Academy from 2011-2013, and publicly endorsed David Cameron. Her later work seemed to capitalise on world events and produce an expensive fanfare: the most empty of which was Anti-Brexit neon sign at St Pancras, I Want My Time With You (2018), or More Passion (2011), the £250,000 neon sign vaguely asking more “passion” of world leaders that was installed in private quarters of 10 Downing Street. I was thus unsurprised when the coronavirus-related exhibition was announced and was prepared to meet the same pseudo-authentic and opportunistic spiel that so disappointingly defined her work of recent times.

Yet, these works have the searing beauty and authenticity of early Emin. While much of the press seems to focus on the fact that these works are centred on Emin moving house after several decades, what I think they capture most strongly is the cloying, depressive form that the home can take during lockdown. Emin told the art newspaper that while she was “used to solitude….these times are scary...dark, and they’re going to get really bad.” This to me is the raw undercurrent of this exhibition. Sleeping With the Night shows Emin in the foetal position on her bed as navy acrylic pours over her, threatening to consume her. This immediately speaks of the cloying anxiety and, as common in lockdown, insomnia and lucid dreams that came with it. Five Hours takes a similar approach. Emin reclines nude in her bathroom, the title telling us she has been in this position for five hours. The monotony of time and the lethargy that has come with this period of isolation is rawly conveyed. Time has lost all meaning, it rushes from us one moment and stands painfully still at others. This period of time for those of us struggling with depression has induced debilitating periods where even a shower feels like a great task. The artist powerfully validates these terrifying feelings in this work which is familiar to her magnus opus My Bed in the way it honestly discusses the impairing effects of depression.

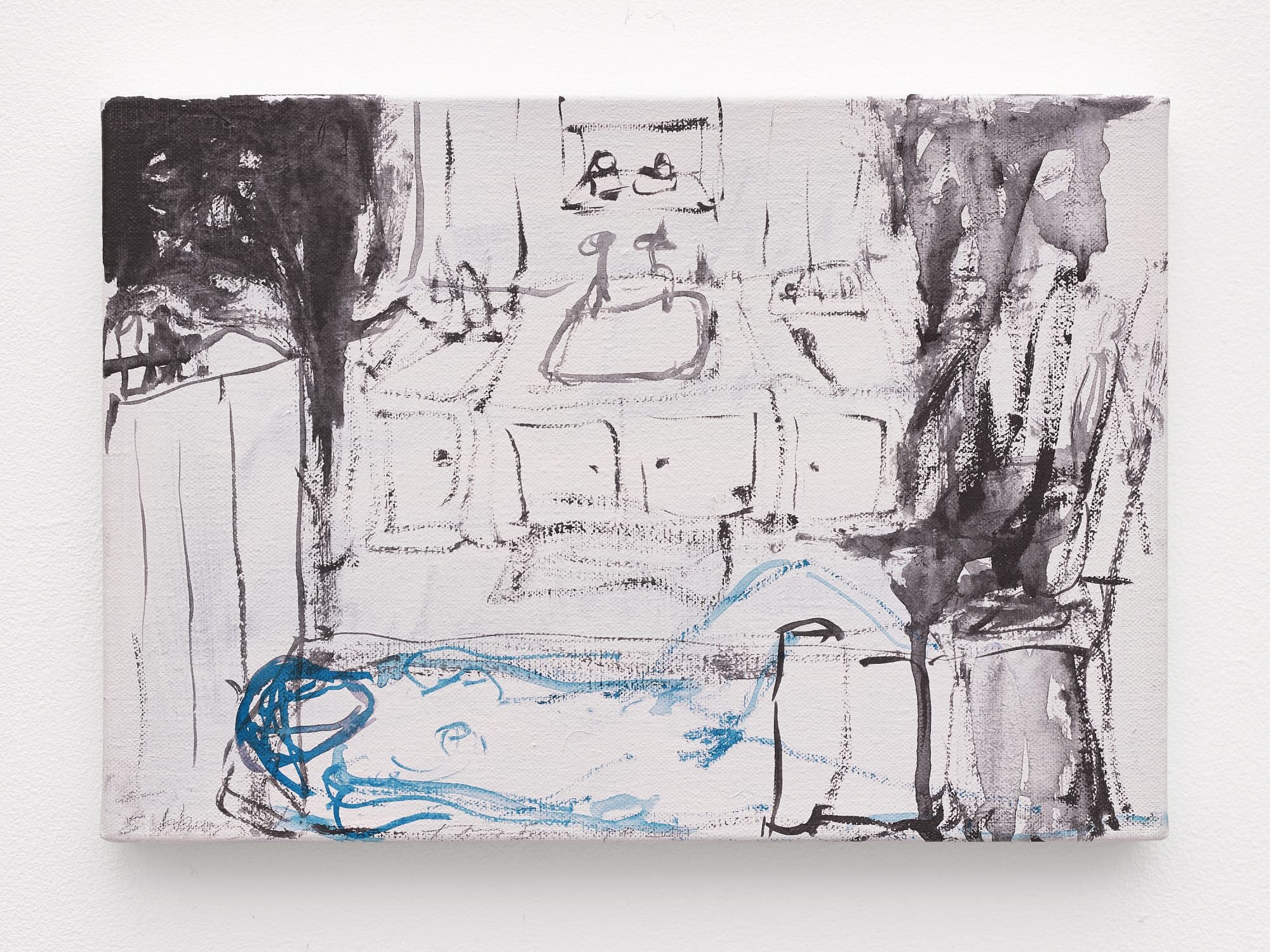

I Dream of Being Here With You and My Mums Ashes and the Ghost of Docket show empty furniture to conjure the loneliness of the last few months. The first shows an empty sofa, the second an urn with the ashes of her mother in her dining room with the spectre of her dead cat hauntingly at the side. This signifies the reality that our surroundings during this period of isolation can change shape depending on our mood. Our familiar surroundings once a source of comfort can change radically under this stagnancy, the empty sofa for Emin becoming a symbol of her loneliness, her dining room suddenly a symbol of loss. The rooms may be still but the titles indicate they fizz with anxiety and longing. This “transference of emotions and place” is powerful, as isolation and all its monotony can turn our surroundings from a source of comfort to something laden with anxiety and painful reflection. My childhood bedroom for instance, once a sanctuary, became a source of painful reflection on adolescent trauma. Emin paints these ideas with a raw and candid beauty.

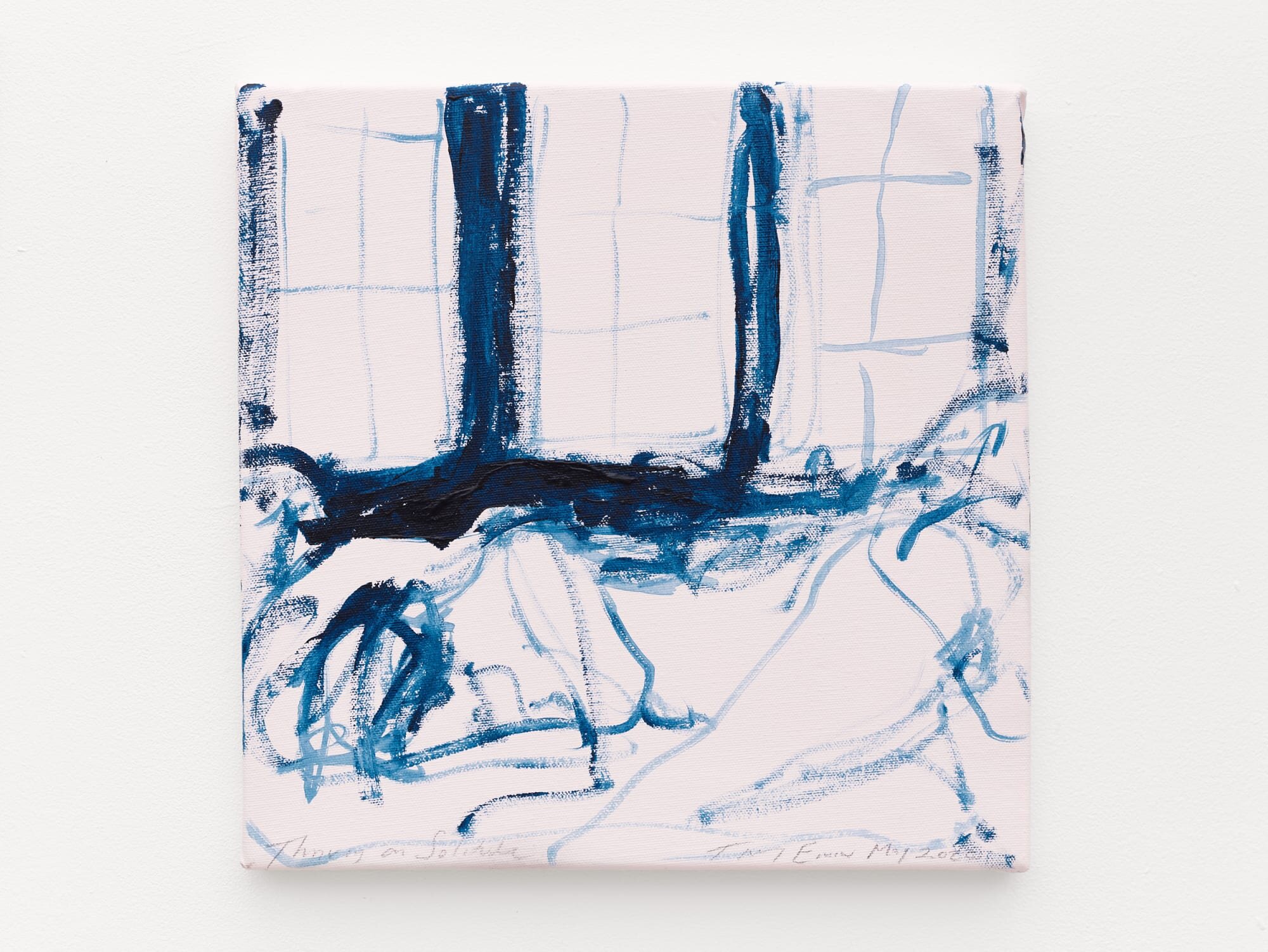

So when Emin titled this exhibition I Thrive On Solitude, I don’t think it was meant literally. Jonathan Jones suggested the exhibition shows Emin “basking” in isolation, but I think the lethargy and yearning of these works suggest Emin is begging an entirely different question. It seems she urges us to modify our own concept of what it is to “thrive.” As smug fresh sourdough and Chloe Ting shred workouts mutated ad-nauseum over social media and condescendingly emphasised a carpe diem approach to the intimidating black hole of free time, Emin’s work here suggests that perhaps to thrive in this period is to simply keep going. Emin recently said, “I thrived in lockdown because I’ve never had so much to look forward to,” which illuminates these works, exposing the depressive lethargy induced by these periods of time, acting as ciphers of endurance. In this respect there is an optimism to the gritty melancholy of this exhibition: Emin says it is enough to just keep going. It’s okay that I haven’t written my first great novel or learnt Mandarin. In the titular work Thriving on Solitude, a naked figure lies sprawled, looking away from the windows. This sums up this exhibition best: the bad, depressive times of these last few months will pass. It is okay not to be okay, says Emin, and for those of us who have struggled with bouts of depression during these times, this is an incredibly powerful and important message.

Ellie Jeans is a fourth year student at the University of Edinburgh studying History of Art.